Travis P here. Our last post on this topic looked at the military training for the very best warriors in both fiction in reality–and please note when we say “best” we mean the most capable, especially able to fight no matter the circumstances, and the most able to resist the psychological pressures of war that cause soldiers to fail to perform when they need to do so. (“Best” in this context is definitely not directly equivalent to “most moral.”)

It’s never been true that every warrior has been elite–historically, a great many nations have lacked the time, money, or knowledge to train any soldier to the highest possible level. And among those nations able to train elite troops, it simply hasn’t been normal to train every last warrior to the highest level. Even the Romans, who hold the record of any historic civilization in terms of the percentage of its population it put in arms, who also adopted a great deal of standardized training in an attempt to make every member of its legions elite relative to other militaries of its time, had its Praetorian Guard. Even the Romans had elite troops who were better than all the rest.

Further posts will build from our base of discussing training to talk about how nations form and supply armies, and how the “supply side” of producing warriors affects how a nation, or a demi-human race, or even an alien species fights battles. We will also talk about types of warriors by weapon and the battle formations they use in more detail, as well as differences between land-centric military forces and those oriented toward naval, aerial, and other domain combat. But for now, let’s stick with observations about types of warriors based on their training. I’d say there are 3 different kinds of warriors by training type with a couple of subtypes each (speaking as generally as I can):

A. Cultural Warriors: Everything they know about fighting they learn from infancy

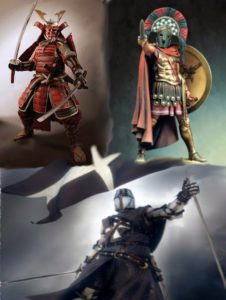

|

| Hereditary Warriors. Image credit: Travis Perry |

- Hereditary warrior castes–paid (professional) cultural warriors: Formal military training is passed down from father to son or is arranged by paid professionals or skilled slaves. Note that unlike barbarians, these warriors require other social classes/castes in their same society to provide them with food and material goods. Samurai, medieval knights, and Spartans were all hereditary warriors–though the Spartans have the distinction of requiring every free male to be a hereditary warrior (Spartan helots–slaves–provided labor to grow the food and produce the the goods Spartans needed to survive). Note that being a hereditary warrior has often been tied to land ownership in the historic past. A certain parcel of land sufficient to supply the food and equipment needs of the warriors was under the stewardship and control of the same warriors (payment was rarely in currency). A special type of warrior caste were various slave warriors, like the Janissaries of the Ottoman Empire. These slaves would be raised from childhood to fight, but would lack the status in their society that samurai or medieval knights were privileged with (and would not control the land used to meet their supply needs)

- Barbarians (or tribal)–unpaid (non-professional) cultural warriors: Nobody in the society receives any formal military training per se, but everyone lives in a harsh environment, where survival is difficult. Everyday life constitutes a type of training–whereas samurai and knights went hunting largely to practice weapon skills that are useful in combat, barbarians hunt to stay alive. And while Spartans and Starship Troopers might spend time in a wilderness area to pass survival skills training, barbarians live in harsh areas every day. Barbarians do engage in various contests of strength and types of play combat with one another, but their training lacks scientific principles of formal study. Think of the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania, our cultural representation of the sea-going Danes and Vikings of Scandinavia, and many Germanic tribes of the Roman era.

B. Paid Professionals: Fighting is a profession they learn and improve after joining the military. They serve for a pre-designated period of time and are usually paid in currency.

|

| Roman volunteer professional soldiers. Credit: about-history.com |

- Volunteer professionals who may or may not see military service as a lifelong career: Formal military training is usually involved and generally happens in adulthood or late teen years. Training is generally well-designed, so paid professional soldiers are usually quite capable–though in fact the quality of these soldiers vary greatly from nation to nation, with poor nations generally unable to give any but a tiny minority of their force quality training. The Roman Empire is well-known for employing this technique, using tax revenues to pay the salaries of its legionnaires. (Note that at one time, roughly 1/8th of all men in the Roman Empire were in the military–which is the highest percentage of paid professional warriors of any historic society). Starship Troopers also portrays a volunteer military made of paid professionals, though they were motivated more by patriotism than pay. Voluntary professionals exist across a spectrum of motivations ranging from pure altruism/patriotism with little concern for rewards all the way to the base mercenary fighting, voluntarily, for pay with no care for the specific cause.

- Conscripts (draftees): Like volunteer professionals, conscripts

usually receive formal training after joining the military, even though they don’t volunteer. At times conscript training has been very basic, but at other times is identical to the training the volunteers get. Conscripts are forced to serve spend time in the military as paid professionals for a limited period of time, often 1-2 years, but sometimes more (or less even). Conscripts have always been known to be less motivated and generally less well-trained that paid volunteer professional soldiers. But at the very least, all of them receive some formal training.

US Army draftees at Fort Dix during the 1960s.

(Photo by Leif Skoogfors/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

C. Part-time Soldiers: Generally only enter active service during a war or national crisis. May or may not be paid

|

| US Colonial Militia Reenactors. Credit: US National Parks Service |

- Militias/Reserves: Militias at times have usually consisted of volunteers, but at times have consisted of every able-bodied person who can fight (usually men). Militias/Reserves may not receive any formal military training, though usually they do receive some, but their training is generally less thorough than full-time professionals, who essentially are paid to prepare themselves for war. Militia units at times have consisted of aged veterans or other persons disqualified from service in a professional military due to age or disability. Called up during emergencies or war, militia or reserve members usually are paid while they are serving.

- Medieval (and other) Levies: Levies were required to fight by obligation, such as duties to a medieval lord, and usually fought only for the duration of a war or for a fixed period each year, and generally served without pay (though their food and other sustenance might be supplied during wartime). They usually received informal military training that was usually not very good or no training at all. (But on occasion levies were quite well-trained.) Often were responsible for supplying their own weapons.

|

| Medieval warriors at the Battle of Crecy, including hereditary knights, levies of bowmen, and mercenary crossbowmen. Public domain image by Jean Froissart. |

If we ask where the Klingons of Star Trek fall in this set of warriors, they share the most traits in common with A2. For them, war is part of their culture, something they celebrate full-time, and is not reserved only for one social class. However, from time to time Star Trek introduces a Klingon who is not a full-time warrior, such as ones who are scientists or lawyers (yet these Klingons still have a warlike mentality). So in some ways, their warriors do form a caste. So Klingons falls somewhere between A1 and A2.

In contrast, the values of individual determination that the Federation cherishes causes it to be a B1 society. But note that the Cardassians of Star Trek have a very pro-military society, yet those who serve are still volunteers who become paid professionals–so their training is type B1, just like the Federation, even though their society is much more militaristic.

Note that ancient Israel mostly fought with levies, especially at first (C2). But the kings of Israel (and Judah) eventually became a permanent warrior caste (A1)–though at times, these kings hired mercenaries from outside Israel (B1). Many other societies have also had complex mixes of warriors the way ancient Israel did.

Societies have layers of ways they drill warriors that relate not just to training philosophies, but stem from their economics and their cultural attitudes about warfare.

Travis C here with some considerations for authors as you map out your story world as well as some illustrations for this topic. Westerners in the 20th and 21st century are familiar with the concept of paid professional soldiers as our modern militaries have evolved into stable organizations. Many of us come from nations where service is a respected profession, with sufficient tax structures and national desire to have standing military forces, and the cultural expectations of how our armies are organized, trained, and utilized have become stable. Soldiering is both art and science, with significant effort spent to ensure a robust, capable, versatile force exists to defend national interests and respond in times of crisis (through use of force and other non-combative means too).

The ingredients to get here were not always present and authors need to evaluate the credibility of their worldbuilding in that light. It’s not that well-trained forces can’t exist in levied/conscript environments, but it would be an exceptional case and in need of justification to make such a story plausible. Let’s look at two examples from the current media, in two very different genres, that highlight some of these challenges.

|

| The Last Kingdom portraying battle. Photo credit: www.gq.com |

Season 1 shows us the complex arrangement of nobles, King, and arrayed foes. Alfred desires to unite the kingdoms of England through his own kingship in Wessex. A man who studies history and thinks logically, he organizes Wessex into individual burhs under the leadership of an ealdorman (earl) who is charged with martial obligations to Alfred. On command, each earlman is required to produce a fyrd, or levy, of soldiers to defend against invading forces. The ealdormen are also responsible for the repair of fortresses, bridges, and other military service. If any refuse, they must pay the king a tax and, for landowners, forfeiture of their lands.

King Alfred must contend with the men like Odda the Elder (a real-life person) who controls the largest fyrd in Wessex and must be convinced to assemble his men against the Danish foe while his younger son desires to reach a peace with the same Danes. In order for the fyrd to assemble, political maneuvering and mutual alignment of interests are needed.

The fyrd itself has limited training and is clearly not ready to engage in combat with the barbarian culture of the sea-going Danes (something like the A1/A2 culture Travis P described earlier). Uhtred’s unique knowledge of Danish tactics and strategy come into the story as he trains the Wessex soldiers to use similar practices against their foes. We see the ealdormen resist him, but ultimately the value of this dedicated training is seen in future Wessex victories on the battlefield.

Author Bernard Cornwell and the television producers do an excellent job of mixing fact and fiction to show us the consequences of a fledgling nation trying to organize military forces against a compelling foe and dealing with limited resources. The distinction between Danish culture, warrior traditions and preparedness, is in stark contrast to the Anglo-Saxon people and the beginnings of feudal society.

Fast forward to the future and interstellar travel via the Skip Drive and we have the setting for John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War. I picked this example because of the unique take on how an army is formed and trained. Instead of the typical young recruit getting drawn into the military and trained from an early age, the Colonial Defense Forces (CDF) are drawn only from the elderly. Those age 65 have DNA samples drawn and sign away two years of their lives to serve in the CDF in exchange for the opportunity to enjoy a life homesteading on one of our colonized planets. Why? Because the CDF needs people who have gained decades of experience to transfer into genetically-engineered, combat-enhanced bodies to fight against the aliens who also desire the same resources we are seeking on those colonized planets.

|

| Image credit: Amazon.com |

The range of possibilities is endless. Military functions will always exist when things are not right and something needs to be done about it, regardless of the cause of that set of circumstances. Characters may be motivated by self-determination, national conscious, a hive mind, a bag of silver, or a desire for the adventure just outside the door. In any case, the author needs to evaluate how to best align their entry into service with the degree and types of training they receive.

Comments

Post a Comment