Especially in epic fantasy stories, human beings or demi humans like elves or dwarves are often portrayed as fighting to the death with total disregard to fear. Creating larger-than-life struggles is part of the appeal of epic literature, but an author should be aware of what takes place behind the scenes in a warrior’s psychology, of what’s normal, to be able to better portray the abnormal. Because people don’t usually fight until the death–they fight until the flight or the surrender.

Many people are familiar with the so-called “fight or flight” response, a state of stimulation caused by danger that can alternatively drive a person to fight or to run away. But as documented in the book On Killing, when fighting members of their own species, not only human beings, but all social animals in creation have a third response–to surrender.

Essential fears

|

| Who is the alpha here? (Credit: Living with Wolves) |

Fear or a sense of being intimidated are the essential emotions that trigger the surrender or flight responses. And there are specific stimuli that trigger this reaction in human beings. Our species tends to be intimidated by opponents who are taller. Which gives a reason why Greek, Roman, and other soldiers wore plumes on the top of their helmets or wore tall hats–in addition to making someone easier to identify on the battlefield, such devices make a warrior appear to be taller. Looking taller didn’t help a soldier fight better in the slightest, but it did increase the chances an enemy will feel the urge to run or surrender. I believe ancient warriors understood instinctively that a helmet plume helped them fight, without having identified the reasons why. Note that tall hats and plumes disappeared when weapon effectiveness from a distance made their payoff in intimidation not worth how much easier a target a soldier using such a hat became. Note also how often speculative fiction has focused on tall warriors—from the cyclops of Greek myth, to giants, to Mobile Suit Gundam, Pacific Rim Jaegers, and Godzilla.

|

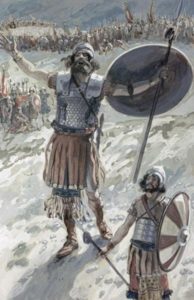

| Goliath (Credit: James J. Tissot–public domain) |

This understanding adds depth to the Biblical account of David and Goliath. Goliath’s size not only made him more powerful, it made him more intimidating. Note that the Bible records that Saul had been in many battles and was a noted warrior long before Goliath challenged his army to send a champion to single combat. Yet in spite of his battle conditioning, Saul had no desire to face off against the Philistine giant himself. This probably went beyond a calculation of the threat the giant posed. The feeling tapped into natural fears–Saul seems to have found Goliath’s height intimidating on a level deeper than reason. And David marked himself as a hero by his ability to overcome that instinct through his confidence in God.

Likewise early firearms, while they had the ability to do devastating damage, were difficult to aim, so had a practical range less than that of bows and crossbows of the same era. Not only was their range more limited, their rate of reload made them slower to operate that crossbows and much slower than bows. In terms of the ability to kill most enemies, bows or crossbows were significantly more effective. But as a weapon of intimidation, firearms that roll like thunder and shoot flames like mythical beasts (the word “gun” is short for “dragon”) were intimidating to enemies in a way arrows could never be. Early guns triggered panicked flight and open handed surrender to such a degree that the gun was far more effective on the battlefield than bows and arrows, even though it was an inferior killing weapon at first. In other words, it replaced the arrow as the distance weapon of choice primarily for psychological reasons. (Note this isn’t true with cannons–cannons actually do more damage than the catapults they replaced.)

Any weapon or method of fighting that taps into instinctual human fears has a greater chance of inducing a flight or surrender response. Some of the main things that humans are afraid of include falling from heights, burning in fire, drowning in water, and loud noises. One of the reasons a cavalry charge was generally effective against foot soldiers came from the intimidation value of the charge itself, horses taller than footmen galloping their direction, their hooves making a roar like thunder. This often caused men on foot to break and run, or surrender, before the horsemen even reached them.

Human beings can be so intimidated by an opponent, especially an opponent with a reputation for ruthlessness and torture of enemies, that they surrender even before any battle has begun. Note that Sun Tzu believed that height of strategy to win a battle based on intimidation alone (The Art of War 3, 2).

If it comes to an actual battle, warriors have proven more likely to surrender rather than run when attacked from the front and behind simultaneously, i.e. when surrounded. When a route of escape is evident (as Sun Tzu recommended a victorious army provide, The Art of War 7, 36), there is a higher tendency for an intimidated army to run. Running triggers an instinctual response in opposing forces to chase after those fleeing the battlefield (like a wolf chases prey or an angry, territorial bull chases intruders on his terrain). Many warriors in ancient and medieval battles were killed after they psychologically broke and were in the process of running away. Ancient Roman armies employed cavalry primarily for hunting down and killing enemies fleeing from the battlefield, rather than for direct combat.

Breaking morale on the battlefield

So the clash of two armies on a battlefield, with both lined up against one another, was not really about who killed the most enemies. The battle almost always ended when one side perceived they would lose and morale broke. And often, especially in ancient and medieval times, more people were killed on the battlefield after an army broke and ran than during what we would consider normal combat, as their enemies chased them down and killed them as they fled.

As a general rule, troops who are poorly-trained are more likely to break. Troops that are highly disciplined and trained over and over again that surrender is a dishonor, surrender far less often, but still do. For example, while all Japanese troops in WWII believed giving in to an enemy was a grave dishonor and many refused to do so, a certain percentage still actually surrendered.

|

| Japanese troops surrendering (Credit: Quora) |

Remember when writing battles that armies don’t fight like video games, with the winner strictly determined by who survives after each side doing the maximum physical damage they can. In almost all battles, the side that lost was the first to break psychologically (which often but not always corresponded to the side taking the most damage), which caused them to surrender or to run away.

Essential fears, morale, and battlefield responses in Prince Caspian

Here are some illustration on the topic. The psychology of warfare is a broad topic with a lot of possible rabbit holes. Like a good engineer, I feel it useful to distill and restate, then proceed with application (sorry fans, no X-Y plots this week). First, Travis P described 3 possible reactions to the stress that comes with combat: Fight, Flight, or Surrender. Second, we provided several explicit examples of factors that may influence each of those reactions, either encouraging the response or dampening it, by tapping into a culture/species’ core fears.

It was an age of lost memory, when the hard people of Telmar came ashore and took control of portions of the ancient kingdom of Narnia. With no Son of Adam or Daughter of Eve to sit upon the throne at Cair Paravel, it looks inevitable in hindsight. But the Telmarines are not ignorant. They know to fear what lives in the woods. Myths and fairytales to frighten children, beasts and demons who haunt that primeval land.

Sound familiar? C. S. Lewis provides us an interesting context for warfare in Prince Caspian, the second book in series order of the Chronicles of Narnia. The Telmarines are castaways who found Narnia by chance but don’t fully appreciate or understand the native creatures, living in an awkward stalemate against further expansion. Telmarines fear the Narnians, fear the legends of the Narnians, even as history passed into legend. That changes when Prince Caspian escapes his evil uncle Miraz and ultimately rises to lead the Narnian forces against Telmar, alongside the returned Kings and Queens we all love.

Both book and movie describe battle quite well, though I will probably rely on the movie for visual effect. After a failed attempt to stop King Miraz in his castle, the Narnians prepare for a last stand at Aslan’s How and the Second Battle of Beruna. King Miraz shows no fear, nor do his nobles appear to, when faced with these legends come to life. His soldiers though… They appear stalwart but have some indications of fear leaking through. The primary weapons to be used against the Narnians are all stand-off: catapults, trebuchets, and ballista. Best to cause damage from afar rather than close with the enemy. They wear masks to intimidate their foes, but maybe it is to give them a sense of equality when faced with minotaurs, centaurs, fauns, and the like. “We are dangerous too” it seems to say.

|

Masked Miraz, dressed to intimidate (Credit: WikiNarnia) |

Before force-on-force battle begins, King Peter and King Miraz face off in single combat, each resplendent in their fine armor. Miraz’s high crest, golden scowled mask, and armored, broad shoulders show a man trying to intimidate his enemies with size. Narnia has similar tactics, with the King’s marshals chosen for size: a bear, a giant, and a crested-helm-wearing centaur already too tall and decked in steel. Who would stand against that?

After treachery ends the single-combat and opens the battle between armies, we notice that the Narnians, a mix of old enemies from the First Battle of Beruna, do not appear to significantly impact the Telmarine soldiers. Maybe some of this happens in the periphery, but by the by, most of the human units fight with coordination and skill. Maybe the Telmarine training regime, combined with a strong desire for revenge against Narnia’s earlier irregular warfare tactics, have caused the soldiers to deaden their flight response.

This changes once the trees show up. When the dryads awaken and the trees come to defend the Old Narnians, Telmarine soldiers flee. We witness some visual evidence of the trees grabbing soldiers on the run, whether because they were easy targets or because, being on the field, they were still considered combatants, we don’t know. The commanders urge their troops to fall back to the river ford, a place where a second stand might be accomplished. It’s hard to distinguish troopers running from tree roots from those conducting a calculated retreat to stronger positions.

|

| Telmarine fear of water (Credit: iCollector.com) |

For authors, I believe an important takeaway is in how we portray the difference between humans fighting humans, and anything other than that. How will people of different cultures, or creatures of different species and natures, act when pressed into battle against one another? In general, for the human race as created, we don’t like killing each other and will take alternate paths out of danger when possible: flight or surrender being preferable to fighting against sorry odds. However, against an adversary not like us, against a cause that will lead to death regardless, you may find well-trained warriors who will press the attack and fight until the end. It may also be a function of degree; the more alike we look, the more likely we are to react in the same manner. Difference may be the key to driving a sacrificial attitude. We might surrender to an elf but press on a hopeless attack against orcs. Alternately, a robot or AI-empowered force might be programmed to never make that decision and always fight through to the logical endstate. How can you flip that? The Machines of The Matrix realize they must ally with the humans to survive a greater third-party in Mr. Smith. In Bright, we see tension between elves, men, and orcs in a modern setting where all three live in the same society and find the main characters navigating that complexity. You have the opportunity to provide the logic of combat responses in any created beings, and have the responsibility to guide your reader into an understanding of how that logic plays in your world.

Comments

Post a Comment