Twelve Monkeys (or 12 Monkeys) is both the title of a 1995 film and also a 47 episode SyFy channel TV series that debuted in January of 2015 and ended in 2018. A caveat to my post here is that I’ve seen the 1995 movie though not the series and will mainly talk about the film, though I’m familiar with the series and will reference how its view of fatalism is different from its source material. Both the film and the series feature a virus that wipes out the vast majority of humanity. And both ponder the issue of whether it’s really possible to change fate. I’ll talk about what I believe the Bible has to say on that topic near the end.

By the way, some spoilers about the film are in this article–in case you’ve never seen it and were hoping to be surprised. (But that was 25 years ago–surely you’ve seen it by now, right? 🙂 )

Cassandra

Both versions of 12 Monkeys do something all my favorite science fiction does; they use the lives of characters to illustrate ideas, to deliberately get the viewer to thinking about what’s actually true. But pondering the nature of fate isn’t new with Twelve Monkeys, in fact, both stories make deliberate reference to the ancient Greek myth of Cassandra in the name of one of the main characters, Cassandra “Cassie” Railly. The myth of Cassandra, for those who may not be familiar with it, features the title figure of the myth being given the ability to accurately see the future by the god Apollo–but because she would not take the Pagan deity as her lover, he also cursed her so that no one would ever believe her prophecies of inevitable tragedy to come (her visions concerned the fall of Troy, by the way).La Jetée

But Twelve Monkeys has a much more recent predecessor than Cassandra. Chris Marker in 1962 produced a short film in French called La Jetée, which featured a central plot very similar to the 12 Monkeys movie. La Jetée is a time travel story from a post-apocalyptic (and rather dystopian) future, back to the past for the purpose of averting the apocalypse if possible. La Jetée by the way means “the jetty” as in a pier, but in French it can also be used to describe an observation platform–in this case it refers to such a platform in an airport, where a young version of the main character witnesses the inevitable demise of his older, time-traveling self. Note the French name of the film also sounds like là j’étais, which means “there I was” or “there I used to be,” the title serving as a play on words referring to time travel. |

| La Jettee poster. Image Source: Wikipedia |

The story in La Jetée is a told by a voice-over narrator while what’s shown is a photo-montage. The overall presentation is très artistique in a style rather uniquely French that did not carry over very much to the American film it inspired. By the way, as a university student studying foreign languages (at that time, Spanish, French, and German), I took a French literature class circa 1993 in which I watched La Jetée. I liked it very much, though I falsely concluded based on the name “Marker” than the man who produced it must not have been French (he was: born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve, who took the pen name “Marker” based on “magic markers”).

Note the apocalypse featured in La Jetée was a nuclear holocaust. The main similarity with Twelve Monkeys was the time traveling central figure in the story, who was a prisoner in his own time, whose strong memory of a woman he saw as a child helped him to make it back to the right time period. Emotionally, La Jetée is a tragic love story of a man finding a woman burned into his memory and the two of them falling in love, with him inevitably dying in the process. Though intellectually, the plot’s firmly about fate and it denies any ability of anyone to change the past. Fate is what fate is.

The Virus

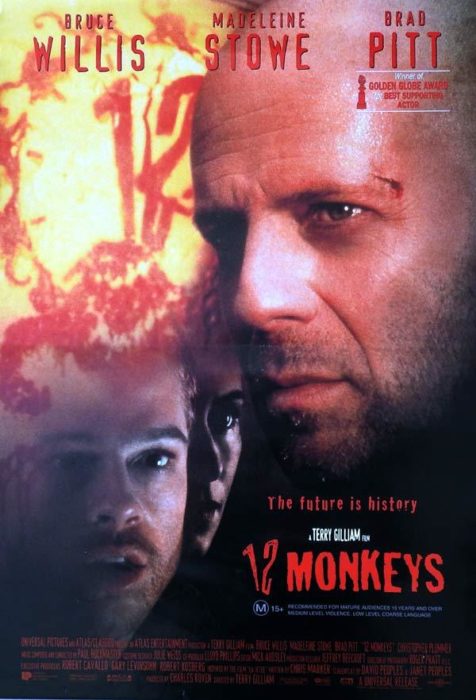

The American film aimed for the exact same emotional and intellectual beats as La Jetée, even though presented in a standard movie format, with major Hollywood stars–including Bruce Willis, Madeleine Stowe, and Brad Pitt. It did offer one major change, though. In 1995, shortly after the end of the Cold War, it seemed that a nuclear apocalypse was highly unlikely (in reality it still can happen and still could have happened), so the plot featured a genetically-engineered killer virus that wipes out most of the human race, instead of a massive nuclear war.

The protagonist and his love interest. Image copyright: Universal Pictures

What’s interesting at the moment of writing this post is the movie’s almost-by-accident prediction that a deadly virus could become a such a powerful threat to the survival of humanity.

|

| The protagonist meets the lunatic. Image copyright: Universal Pictures |

But could a powerful virus disrupt the human race and change it forever? Why, yes, at least to a degree. We’re disrupted right now. Though the changes won’t last forever and may not even have much of an effect even one year from now.

But then again, even though no human being really knows the future, it’s probably safe to predict other international viral pandemics will take place. The question is simply where and when and how large the effects will be. With the related question of how human beings will react to these threats.

Viral Fate

So is death by deadly virus part of the inevitable fate of the human race? Is this something we should fear? Would this be worse if someone did this on purpose? |

| David Morse as the scientist who deliberately releases the virus. Image copyright: Universal Pictures |

Viruses not as deadly generally spread much more easily, especially if some people carry the virus but don’t show symptoms. Which is how Covid 19 works. But of course Covid is deadly enough to require efforts to contain its spread.

Since it’s rather built into the nature of viruses that they by themselves can’t wipe out 99% of the human race, even if a human being were to jigger with them, I would say we should not be in terror of viruses, even though viruses are going to keep popping up. Though it makes sense to take reasonable precautions. Such as washing your hands. And following other guidance given out by public health officials.

Fate Fate

But wait a minute–don’t we Christians believe God knows the future? This is established in the Bible in many places, for example, Isaiah 46:10. Don’t we believe God even has determined in advance when we will die? Among other passages, reference Hebrews 9:27 for this doctrine. So why should we try to prevent our own deaths if that’s already been determined?Could it be that like La Jetée or Twelve Monkeys we can try to change how events turn out, but in the end, what’s going to happen is what’s going to happen? So we actually have no power to change our own destiny?

Note that the TV Series Twelve Monkeys takes a different approach about changing the past via time travel, i.e. changing fate. In the series, changing fate is not impossible. It’s just very, very difficult (for an explanation, look under Development in the linked article about the series).

So which of the two 12 Monkeys views is correct? Is it possible to change our destiny, but difficult? Or is it impossible?

C.S. Lewis, so brilliant in so many things, offered an opinion of sorts on this subject in story form. In Prince Caspian he has Aslan tell Lucy when she asks what would have happened had they obeyed him better: “To know what would have happened, child?…No, nobody is ever told that.” Which would seem to imply that the choices we actually make are the only ones that really matter. As if choices we didn’t make could not have ever really happened. As if everything we do is already pre-determined.

By the way, I’m not saying Lewis believed human actions were all pre-determined. Just that the one particular bit of dialogue in Prince Caspian sounds that way. In general, Christians have rejected complete pre-determination and have maintained human will must somehow include real choices, or much of our Christian practice would make no sense. Such as sharing the Gospel in hopes that some will believe.

Though of course some Christians have believed that God pre-determined all actions anyone could take. Though such a position is more a characteristic of people with a deterministic and cause-and-effect view of the universe acting strictly according to natural law, without direct intervention by God. Deist Albert Einstein was and atheist Sam Harris is a strong supporter of total determinism of human actions.

The Bible on What Could Have Happened

Surprisingly, Lewis seems to have goofed when he had Alan tell Lucy nobody is told what would have happened. Because the Bible records in I Samuel 23:9-13 that when David was fleeing from King Saul and occupied the town of Keilah, that the men of the city would turn him over to Saul. So David packed up and left the city–and was never turned over. So David was told what would have happened, even though it didn’t happen.So the Bible seems to play it both ways–it declares God knows all things and has established what will happen. Yet it calls on us to pray that God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven–indicating it isn’t being done that way now.

It would seem the Bible supports the idea that changing the past would be possible, if we ever got a time machine and had the opportunity to try. Though I suspect it might be difficult.

But can we make real choices? Can we in effect change our fate? It certainly seems we can–or why else would David have been told what would have happened?

Conclusion

So since what you do matters, wash your hands and take some reasonable precautions versus Covid 19. 🙂As for Twelve Monkeys, have you seen it? I’d especially be interested in hearing the thoughts of people who’ve both seen the movie and the TV series.

Are there other sci fi stories that talk about fate in the context of a viral pandemic? Or other time travel stories you’d recommend?

Comments

Post a Comment