Readers, the Guide to War continues! With Balance of Power this time–though the title doesn’t quite mean what it seems to mean.

Note that I will be leading off these topics with commentary that fellow author Travis Chapman (who, by the way, is an instructor of Nuclear Engineering and Thermodynamics at the US Naval Academy) is going to review and tweak, to which he will add specific “case studies” or illustrations that I will review and tweak, my words at the beginning of a post that will transition into his words at the end.

To get back to “balance of power,” please remember that the first post I wrote on this topic I now wish I’d called “part 1, Basic Drives” (or maybe “Basic Impulses”) because I tried to identify the root urges that cause people to organize themselves to fight. That is, what it is they are trying to achieve or obtain.

With the title “Balance of Power” I’m picking out the key element of what I may call in the book “Reasons for War” (or maybe “Reasoning Leading to War”)–but which I won’t do now because I used “Reasons” in the last post. The particular phrase “balance of power” is getting special attention because something happens to groups of human beings, whether tribes, kingdoms, or large modern nations, when there are a number of them in contact with one another and war is a possibility.

Nations (or tribes, etc.) in such cases have to pay careful attention to not just to what they want, what drives them in the direction of seeking war–they have to pay careful attention to their own relative power verses their enemy or enemies. That means they need to be able to evaluate the nation they plan to go to war with in terms of its ability to fight–but they have to keep in mind what other nations around them are doing, in case any of them might intervene, lest their declaration of war end in disaster.

This kind of reasoning is briefly alluded to in the New Testament (Luke 14:31-33), in which Jesus mentions how a king calculates if he can beat an army of 20,000 with 10,000 soldiers and sends off a delegation of peace if he can’t (Jesus used this kind of calculation to illustrate a point about being a Christian disciple). This case is representative of the simplest possible kind of war–one nation against one nation.

Credit: Hendrik Willem Van Loon

Note though that it was absolutely normal 2,000 years ago (and even long before that) for nations to engage in calculations of war regarding a wide variety of things, including in particular the balance of power. A great deal of military strategy involves (and has historically involved) considerations of how one particular nation sizes itself up against others–the minimum calculation stemming from one nation verses one other, but which in most cases extends to include other nations (tribes, etc.) in the area. Because with very few exceptions, humans fear all their neighbors uniting against them.

This leads to a number of observations, the first of which was alluded to by in Luke 14:

1. A nation will generally negotiate with an aggressor nation because of fears of losing a war. Or if they feel they could win the war, but the cost of winning is too high.

So while some people claim human beings naturally negotiate and then go to war when the negotiations are unsuccessful, the actual situation is more complex. Just going to war without any negotiation seems to be the first impulse of warlike nations–but a rational analysis that they could lose the war (which provokes healthy fear), brings them to the negotiation table. And only then, after negotiations are developed as an instrument to avoid the bad consequences of war (but not to avoid conflict itself) does a breakdown in negotiations start a war.

2. At the risk of sounding obvious (but for a purpose), nations generally choose to engage in war when they believe they can win, when the balance of power is in their favor. No human group goes to war simply because they have a military that’s superior (or perceived superior) to a potential enemy. But once the basic impulses (or reasons) for war as explained in the last post come into play, nations with superior military forces are much more likely to engage in war than weaker nations. This idea brings a couple of interesting corollaries:

a. Totally pacifistic groups that survive as such generally have little impact on the balance of power among surrounding nations–that is, often enough, being weak reinforces being meek.

b. Nations are more successful with negotiations when they don’t need them (because they are strong enough to win anyway).

c. Assessing the power of one’s own nation versus that of other nations is a major activity for military planners, because it’s vital to know if ten thousand really can beat twenty thousand.

3. Nations sometimes decide to go to war because they miscalculate the balance of power, especially in overestimating themselves against their enemy(ies). This is why Sun Tzu in the classic Chinese work on warfare, The Art of War, lists spies as the most important part of any Army (The Art of War, chapter 13)–because a good spy network can determine if circumstances justify warfare (or if they don’t).

The WWI Balance of Power Chain Reaction–from a public domain cartoon of the period.

4. Nations often seek alliances with other nations if they perceive themselves to be too weak to maintain a balance of power on their own. Once a balance of power is established among groups of nations through alliances so that both sides or all sides see themselves are roughly equal to one another, they are less likely to go to war. Yet, as in World War I, this creates a situation in which a single relatively small incident can cause an entire alliance to go to war over any particular friction between any of the various parts of the coalitions involved. (As the number of relationships grows, the chance of a spark does not grow proportionally, it’s more like exponential growth.)

So a great deal of activity among nations, both in the real world and in fiction, seeks to establish or maintain a balance of power–and when they fail to do so–or even if they succeed, the problems stemming from balance of power considerations often lead to warfare.

Note when we’re talking about balance of power at the national level, there are three basic ways a nation can evaluate itself: 1) Below average to some degree, 2) at parity with surrounding nations, and 3) being in a state of greater power. “Power” might not be limited to ability to conduct warfare–it can also mean economic power, perceived cultural or ethical power or position, numerical power (greater population or controlled territory), or geographic power (i.e.,holding territory that has the most value, like key mountain passes or navigable waters). Obviously a nation (or any group of nations) might possess a bit of any of these, or all of them.

So with the three basic tiers mentioned above, we see the following inherent conflicts:

- Lower nations trying to bring down those in higher positions

- Lower trying to achieve parity with others

- Lower fighting for the scraps between each other–or adopting a pacifistic attitude

- Higher stations trying to hold their positions against internal disruption

- Higher stations trying to eliminate potential competition from below

- Parity nations try to climb one rung higher than a peer

- Parity nation trying to pull up a lower nation to their level (often via an alliance or coalition)

This complex set of relationships above is in fact based on one nation against another at any given moment and doesn’t list every possible situation: the dynamics of alliances and coalitions are generally even more complicated, but have many of the same elements. Both sides of a potential conflict have a story to tell about why they chose to go to war and their own perception of how things reached the point of conflict–which provides plenty of story material for any author.

Travis C here. Any nation (and we’ll assume a nation here, but it could be any organization of entities) will have a certain calculus going on as they consider their position on the hierarchy of power. You should realize it’s calculus too, not just basic algebra, and a good deal of statistics. In the modern world, it is often literally math, with military planners doing calculations of force, weapon effects, measuring changing conditions, and mapping varied courses of action and their likelihood of success or failure. For fantasy literature the calculus will likely happen at the planning table and in the minds of key stakeholders weighing the odds (think of King Theoden stating Rohan will not risk open war). I propose that in most science fiction settings you might add an element of AI support to our modern practices (cue C3PO calculating the odds). Only you will know to what degree you’ll need to analyze all sides of the conflict to determine the impact it has on your story.

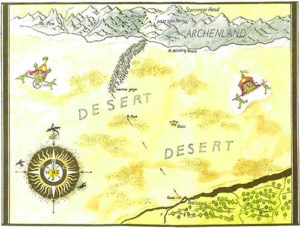

The desert between Calormen and Archenland.

One of my favorite examples of this calculus is found in C.S Lewis’ A Horse and His Boy. We witness a peek behind the curtain as Lewis truly shows, not tells, the analysis of nations when we meet Shasta in the company of the Narnians while in the nation Calormen’s capital, Tashbaan. The Narnians suspect Prince Rabadash of ill dealings and speculate what might occur should they escape Tashbaan. Narnia is no match for Calormen sword for sword (differing relative positions of martial power). However, Narnia and ally Archenland are protected from the brunt of Calormen’s army by geography. To launch a major campaign against Narnia, Calormen must either cross a vast desert (logistically challenging) or embark by sea for an invasion (likely to be met with resistance ashore and hard to pull off at such a distance). The Narnians conclude the risks associated with escape are worth it; they doubt Calormen will retaliate in any meaningful way.

Now we jump ahead and learn the Tisroc, supreme ruler of Calormen, will back a minor expedition by Prince Rabadash to take the small kingdom of Archenland by way of the same desert. A small force may successfully cross the desert and maintain sufficient strength to overthrow an unexpecting Archenland. The Tisroc, without Prince Rabadash’s knowledge, accedes the venture may not carry, but if it does and Rabadash conquers Archenland, then Calormen can slowly build up a military force on Narnia’s doorstep, making way for a future campaign. He also weighs his relative political strength in Tashbaan when he admits that should Rabadash fail, he’ll write the whole thing off as a boy’s rash temper. Surely he knows the Calormen news cycle to assure himself of an evening headline “Wild Prince Rabadash Goes Off The Handle; Archenland Protests Military Exercise In Desert” is one he can recover from.

The Tisroc…

Lewis uses the varied geography between Tashbaan and Castle Anvard to drive the major characters until we reach a satisfying conclusion. We see the roles of individuals, small units, and ultimately three major nations, two in alliance, all collide in a beautiful story that displays evidence of a well founded conflict between nations.

It’s also worth noting that Lewis plants a seed here. The argument of the Tisroc, that Narnia can be taken by seemingly unnoticed infiltration, comes to pass in The Last Battle. Small gatherings of Calormen, under the guise of merchants, slowly gain a foothold in Narnia and ultimately allow the receipt of Calormen’s army by sea in the taking of Cair Paravel. A strong analog to the way that seemingly minor, yet persistent, sin can gain a foothold in our lives.

Since Travis P opened us, I’ll close this one out. We’ve combined efforts and hope to bring you an outstanding series on the nature, conduct, and consequences of the spectrum of conflict we call war. We have an outline of topics to cover in a shared voice. We hope to do this through two contexts: first, as writers of speculative fiction, and second, as authors of fantasy and science fiction in particular.

Hopefully you can keep your Travises straight. It’s going to be a great journey together!

Comments

Post a Comment