Today I’m re-launching a series of posts I did for Speculative Faith onto my personal blog. A series I did not finish there, but which I plan to finish here. My goal is to make a comprehensive guide to warfare, from beginning to end, from fantasy war based in the legendary past, to futuristic science fiction conflict. And we’ll start at the beginning–reasons. Why does anybody go to war in the first place? What causes conflict? And how do you use that knowledge to write a better story?

When discussing causes of human behavior in general, you’ll find that there’s much speculation and disagreement–and the subject of war is no exception to that. It’s not even universally agreed upon if war is natural to human beings. For almost all known societies over the entire world throughout all of known human history, at least on occasion wars are fought and at least a little formal training for warfare exists. Though it is also true that human beings in general show signs of having a natural aversion to killing one another–if we did not have such an aversion, training warriors to fight would not be necessary.

In terms of why wars begin, the Wikipedia article on war fairly represents the topic when it lists seven major categories of theories of reasons wars begin (Psychoanalytic, Evolutionary, Economic, Marxist, Demographic, Rationalist, and Political Science), many of which have sub-categories. In other words, there’s a lot of disagreement about this topic.

This Writer’s Guide for Speculative Fiction authors (which is focused on science fiction and fantasy) takes the view that warfare among human beings stems from aspects of human nature that are common to all human societies, but which require certain societal elements to exist before they can be expressed in warfare. In spite of occasional allegations of completely peaceful societies, there has never been a human society which has no concept of crime in general and murder in particular. Murder–in which one human being kills another for reasons the society does not see as valid–is very rare in some societies, but exists everywhere human beings live. Likewise, even in societies that practice sharing of resources, it still happens that people disagree over who gets what at what time on occasion, leading to conflict. Even in tribal societies that are very egalitarian, at times there is disagreement or even conflict about who will be in charge of a particular action. And even in tribal societies without a formal law code, it’s true that sometimes fighting occurs within the group over perceived injustice–usually relating to issues of crime, yes, but fighting can also erupt when a group of human beings cannot agree about what is and is not just or fair or right.

Murder, fighting over resources, fighting over position in a society, and disagreement over the rules can each be phrased in terms of a human trait that is the primary cause of each of these actions. While hatred is not be the only cause of murder, it’s a major one. While it may be possible to fight over resources without greed or envy, feelings of at least envy usually accompany such a fight. Seeking prominence over others is usually (fairly) associated with pride, and disagreement over the rules appeals to the innate human sense of justice. Hatred, envy (or greed), pride, and justice–all human societies express these traits to some degree or other. Note that the first three of these traits are generally seen as vices–and justice itself can be a vice, if misapplied.

Though not all human societies go to war, even if all societies have the traits that cause war. But even societies that don’t go to war, if they were invaded by others, would be able to define what’s happening based on the principles they already know. That’s true even if they are shocked by the level of brutality involved. For example: “Those people are murdering us to take our water!”

In speculative fiction contexts, it may be that fantasy races or alien species literally would have no concept of war and wouldn’t have any conflict within their societies either. Such people probably would not even realize they should run away when attacked, not immediately anyway. But in discussing warfare, let’s start with the baseline reasons of what is known about human beings first and then afterwards adapt that to non-human societies.

So if the reasons behind human conflict are found in all human societies, why is it that not all societies actually go to war?

The societies that don’t go to war fall into two groups: 1) tribal societies that occupy a niche in which war is unlikely 2) deliberately pacifist societies that come out of warlike societies and which consciously reject war.

The number 2 societies probably require the least explanation. They usually are part of a religious order that teaches that all human being are valuable, so killing any of them is wrong (think Amish or Mennonites or groups like them, or various monastic orders, or Jainists)–or on occasion are non-religious organizations that have high intellectual ideals that include rejection of violence (like some Israeli Kibbutzim). People raised in these societies who are taught to believe war is wrong usually live up to their beliefs and refuse to go to war.

Number 1 societies include tribes that are so geographically isolated that it’s very hard for them to make contact with other groups, let alone fight them. It also includes groups that occupy an ecological niche that other groups are not interested in. Example for both: Imagine a tribe living in a small oasis in a desert which is surrounded by well-watered lands–it may be that other tribes prefer to fight one another over the well-watered lands rather than cross the desert, leaving the oasis tribe to live in peace.

Note the existence of isolated groups that do not engage in warfare at all is the reason some anthropologists argue war is not natural to human beings. They imagine that the original state of the human race consisted of this type of isolated tribes that did not ever fight each other–only later when, say, agriculture was developed, could a society have surplus food to pay people to train for warfare full-time.

While it is true that desperately poor societies cannot afford to pay for a warrior caste, some tribal groups have existed in which everyone (or in most cases, every male) in the tribe was a warrior. That has been especially true for groups that live in areas that make for easy travelling and which have resources which are easily stolen (think the animals that pastoral nomads keep). These groups are usually the among the most warlike of all human beings.

So it seems there’s an element of necessity in who is and who is not warlike. Those who are vulnerable to attack are more likely to be aggressive (in self-defense) but the issue of resources also raises its head here.

Fighting over resources, whether water or food or even gold for societies that use precious metals, seems to be the primary reason for people to go to war. To either take or defend what they perceive they need. Humans also seem show a preference for not fighting over resources if they don’t have to–that is, societies which are vulnerable to loss of resources organize themselves to defend those resources, but ones who can obtain what they want or need “for free,” are much more peaceful–which is where the natural aversion to killing others seems to come into play. It does seem to be true that while some individuals may chose to kill (in the criminal sense) in any society, only societies who perceive they need train themselves in warfare actually do so. And that perceived need is mainly based on access to resources–though again note that almost all humans, historically speaking, have perceived a need to organize to protect resources, so this isn’t anything unusual. A pacifistic society is much more exceptional than a warlike one.

Note that while hatred of others may cause one person to kill another within a tribe and relates to a reason for warfare, it’s actually not usually the main cause of a war–but it can be an important catalyst. Especially because human beings are very quick to define other humans in terms of those who are part of our “in-group” and those who are part of an “out-group” (quotations are there because these are standard terms, though not necessarily ones I prefer). Humans find it much easier to hate someone who is not part of the in-group. When humans start thinking of the out-group as being less than human, which may not be limited to but certainly involves hating them, it becomes easier to go to war against them. Hating another human being to the degree that they are thought of as less than human, or another group of human beings, helps overcome the natural aversion to killing them.

Some people would elevate the fact humans divide into groups easily as a major cause of warfare. This tribalism in modern form can bleed over into racism and extreme nationalism, which certainly have been involved in many wars. While I agree that tribalism is important, that’s because we humans find it easier to hate those outside the tribe than those in it–tribalism itself is not the issue as much as hatred is. Without hatred and the willingness to kill empowered by hatred, tribalism or nationalism is mostly harmless–they amount to trivial things like which flag you wave at the Olympics.

Note that envy over resources in an environment in which conditions are harsh can easily become greed, in which one or both sides of a fight actually have enough to survive, but are striving for more anyway, hoarding gold like legendary dragons. Greed is a major cause of warfare–one nation or tribe seeking to take from another something it may not really need, but definitely wants. Think of Cortez’s conquest of the Aztecs, or even more so, Pizarro and the Inca, in which lust for gold, land, and women drove the Spanish conquest forward.

Pride (or prestige) as a motivation for warfare is a bit more complex. Societies that develop a warrior class usually laud praise on their warriors–and rightly so under many circumstances. They are, after all, protecting the in-group, and providing for resources people either need to survive or don’t need but want anyway.

There’s quite a bit to be gained in being a successful warrior in terms of how well others treat you. Certainly Cortez and Pizarro not only were greedy for gold, they knew in the warlike society of Spain, they would be admired as conquerors. They’d be given prestigious titles–they’d be seen as heroes (and they were then, though not anymore). Those who like to put things in evolutionary terms say the prestige successful warriors gain gives them the opportunity to produce more children, which they see as a basic drive. While it is certainly true that the prestige warriors have heaped upon them may help them marry and reproduce, the historic warriors who have reproduced the most did not have women flock to them because of their prestige as much as they took the women they wanted because of their desire to have them (greed/lust)–think Genghis Khan.

While it is sometimes true that a warrior caste will seek to go to war because of the prestige or honor involved (honor is how they’d put it), going to war simply because they can (like Klingon warriors) is actually not as common as fighting over resources. But having a warrior caste with intrinsic reasons to fight can certainly be a catalyst for a war.

Fighting for justice is not often listed as a reason for warfare by experts on the topic, but should be. When we think of wars of religion, weren’t people fighting because they think their religion is right (just) and the other religion (or lack of religion) is unjust? When revolutions happen, such as the French or American Revolutions, wasn’t part of the fighting taking place over perceived injustices and abuses? Like taxation without representation? Or anger at the abuses caused by the so-called divine right of a monarch?

Note that a sense of justice can be a catalyst for warfare in a different way that other traits listed here. People want to think of themselves as being in the right and it is much easier to defend violence that is perceived to be honorable than to do so for other reasons. Please recognize that’s true even if you assume there is such a thing as just war (and I believe there is). The existence of just war does not mean that every single appeal to justice is actually fair or true.

Often nations have a stated reason for war that’s different from their actual reason. The stated reason for the Crusades was that they were about justice–Muslims were heaping abuses on Christians in the Holy Land and furthermore had no right to be there as far as the Crusaders were concerned. Yet the actual reasons had a lot to do with overpopulated European territories, looking for lands (and resources) elsewhere, a warrior caste in Europe itching to go war (for the prestige involved), and the fact it was easy to see the Muslims as an “out-group,” not only because they were perceived as racially different, but more importantly because they did not share the Crusaders’ religion.

The “real” causes of the Crusades has been debated widely and will continue to be debated. Even if we grant that the Crusades really were about perceived injustice (a.k.a. a war of religion), it’s ridiculous to think Cortes and Pizarro invaded the Aztec and Inca Empires in order to right the wrongs those empires perpetuated, including their perceived errors of religion. Yes, the consquistadores probably felt better about themselves bringing priests along to justify some of their actions in the rhetoric of spreading their faith (which they would see as undoing injustice)–but their greed for gold, land, and women is well-documented as their primary motivation.

The “real” causes of the Crusades has been debated widely and will continue to be debated. Even if we grant that the Crusades really were about perceived injustice (a.k.a. a war of religion), it’s ridiculous to think Cortes and Pizarro invaded the Aztec and Inca Empires in order to right the wrongs those empires perpetuated, including their perceived errors of religion. Yes, the consquistadores probably felt better about themselves bringing priests along to justify some of their actions in the rhetoric of spreading their faith (which they would see as undoing injustice)–but their greed for gold, land, and women is well-documented as their primary motivation.

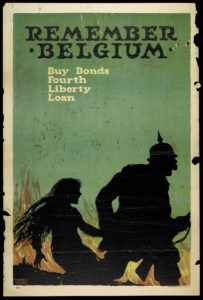

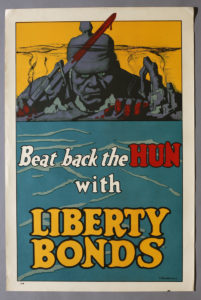

To leap to a much more recent example, did the United States really enter World War I “to make the world safe for democracy” (as US President Wilson stated)? Well, partially–the motives were to protect American shipping and businesses, but also there was a sense of justice involved, especially over widely-reported German abuses in Belgium (called in the press at the time, “the Rape of Belgium“). And also important was a wave of anti-German hysteria that swept through America–hatred of the other, the Germans, our enemies, the “Huns” as seen in the classic poster. (Note the imagery of the “Hun” is of a savage, barbaric invader from the East.)

You’d find if you dug into details that there were layers of motivations for the entire country, the basic causes interacting in a complex way. And also that the motives for going to war for a single soldier varied a great deal from soldier to soldier in that conflict–which would be likewise true for almost every war. Motives probably even varied for the same individual soldier at different moments.

And while the reasons for a nation going to war are more complicated than those of a single soldier in that nations often primarily seek to gain what they want by negotiation and only go to war when negotiations break down (as reflected in the war theorist Carl von Clauswitz saying, “war is the continuation of politics by other means”), the same basic reasons apply to all wars, even when political factors not named in this post are also involved (such as a nation overestimating its ability to win a war).

I’d say there are four basic causes of wars, listed in order of actual importance for most conflicts (though the order does in fact vary from war to war and person to person as mentioned above):

Resources (or as a vice, greed/envy)

Tribalism (as a vice, hatred of other groups)

Prestige (pride)

Justice (as a vice, false justice or religious extremism)

In order of stated importance, publicly declared importance, reasons for war are usually:

Justice (nations usually proclaim themselves to be right–and only on occasion actually are)

Prestige (calls to service and self-sacrifice are common, especially in modern wars)

Tribalism–hating the other (though some wars have used so much propaganda against enemies that hateful tribalism or nationalism is openly more important than number three)

Resources/greed (most societies talk least about their actual reasons, which are usually-but-not-always about possession of territory or other material things)

As you apply these principles to stories, think about how these motivations play out for the individual human beings involved, which may or may not be the same as collective national or tribal reasons to fight. Note that stated reasons for war are often different from actual reasons. Writing a complex mix of motivations for a war makes for a more realistic and more interesting story.

To briefly mention how to apply these principles to races or species who are not human, while it might be interesting to attempt to invent reasons for warfare that have no connection to how human beings behave, it’s probably best to simply change the order/priority of war reasons that also apply to humans. It will seem more realistic (to human readers anyway 😉 ) but can still provide some interesting twists.

What if, for example, other species always stated their actual reasons for war openly? Or if a fantasy race had a much stronger sense of justice than human beings have so they don’t ever care in the slightest about resources they could gain? Or if a race had no tendency to be tribal, but still fought for other reasons? Or if they had no actual aversion to warfare in the first place? Or on the other hand, what if a non-human society were naturally non-violent because of an inability to hate others (which is not necessarily the same thing as being good and pure in every way), yet learned over time it was necessary to defend themselves, taking much more time to process what war is than humans require?

Please excuse the length of this post, I’ll strive to keep future ones shorter, but I hope you’ve found it informative. With so many academic opinions on this subject, I don’t imagine for a moment that everyone will agree with what I’ve listed here. So what are your thoughts on the reasons why people go to war?

Comments

Post a Comment