This post is inspired by a specific question from one of the readers of this series. The nature of the question is worthy of a specific answer, yet this particular topic was not part of what I'd originally planned to cover. It finds it's places at number 8 in the series due to an earlier error that skipped that number.

Let’s make a few things clear up front: 1. What is most life threatening and what is most painful are often not the same thing at all. 2. What is the most gruesome to see is not necessarily the most painful, either. 3. Different people experience pain differently, so coming up with any absolute scale of painfulness is impossible. However, there are certain tendencies that have been noted in how people react to pain, allowing us to make some general observations. Let’s take the topic of how different people experience pain first.

Note this discussion will become a bit gruesome, though I’m not going to show any graphic pictures. But if you’re of a very sensitive nature, you may not wish to continue reading.

Pain Tolerance

“Pain threshold” refers to whether a person feels pain at all–and in fact not all human beings are the same on this topic. Though most of us are similar, barring neurological disorders that interfere with feeling pain. What varies a great deal more than pain threshold is “pain tolerance”–that is, the degree to which a person can put up with pain after agreeing that it’s there.

Some observations include the somewhat controversial notion that men tolerate pain better than women. That is, for the same injury, when rating how painful it is on a scale of 1 to 10, men in the United States in particular and in various international studies will rate the pain with lower numbers than women will use. Cold bath tests, in which someone immerses an arm in ice water (which is painful but does no serious harm) consistently shows men on average keeping their arms immersed in the cold for longer periods of time than women will tolerate.

How much of this is cultural, male machismo merely refusing to admit to pain that they feel as much as women do? That’s both debatable and debated. My own personal observations from the 12 years or so I was a medic in the Army Reserve and periodically would treat people, in particular with vaccinations, or would draw blood for testing, is that among soldiers (not the general populace) women were more likely to complain about the pain of a needle. Though some individual women didn’t complain or even flinch at all, while some individual men kicked up quite a fuss.

It’s not uncommon for women to point out that if men had to give birth, there’d be a lot less children in the world. 🙂 But direct comparisons between similar conditions, such as a woman having kidney stones verses a man having kidney stones, does not actually support the idea that men would be inherently less capable of managing the type of pain associated with childbirth.

In some cases the difference in pain tolerance is clearly physical. People with a definite hand dominance (a group which includes about 99% of people) show a higher resistance to pain in their dominant hand than their non-dominant hand. I’d also put in the category of physical differences that indicates redheads seem to experience pain differently than non-redheads, with them being less sensitive to stinging skin pain and spicy food on average, but more sensitive to cold and bone pain like toothaches.

Scientific studies seem to show at least some of the differences in how people react to pain is physical, but it’s hard to rule out cultural factors. Cultural factors may explain why one study found that African Americans consistently tolerate higher levels of pain than white people.

My own observations agree with the idea that pain tolerance is at least somewhat cultural, because I’ve observed some nationalities, say Afghans–regardless of their skin color–tolerate pain much better than other nationalities (i.e. most Americans). I think the expectation of how much pain a person can and will tolerate is affected by life experience–people raised with pain in their environment usually learn to tolerate it better.

Note that scientific studies also show athletes tolerate pain better than people out of shape. This reinforces my idea that conditioning to pain as experienced in cultures with significantly lower levels of luxury than modern life actually has something to do with training the body. Perhaps the exposure to the pain involved with working out prepares people to face much greater pain. Or perhaps a healthy body (as in very fit) is inherently better at coping with pain than an body that’s out of shape.

Related perhaps to our observation about athletes and/or cultural exposure to pain, psychologists have also observed that a state of anxiety can make pain worse. People with chronic fear or anxiety will experience pain more deeply than someone who feels confident and who deliberately relaxes during pain (such as by focusing on breathing, as is taught as a method to assist with childbirth).

One general observation we can apply to this discussion, especially since many readers of Speculative Faith are fantasy authors: We can expect people from cultures like our own Middle Ages or Ancient period to have higher pain tolerance than most people today have. Of course, this wouldn’t apply to absolutely everyone. While medieval peasants, the vast majority of people, might live with pain in a way most modern people can’t imagine very well, not everyone was a peasant–or a highly trained warrior either. The Middle Ages had monks and scribes and tailors, etc., whose reaction to pain probably would be more like a modern person’s than the majority of people from their own time.

Most Painful Wounds

To kick off this section, I’m linking a website that get’s what’s painful largely wrong. (I’m doing so as a means to discuss why the site has it wrong.) The linked set of pages, which are dedicated to the kinds of injuries found in horror movies, appears to be listing injuries based on what is horrible to watch on film, rather than what really hurts. In a counting-down-from-ten format, this is what the site lists as the ten most painful injuries:

TEN (10.) Burning, 9. Slit throat, 8. Eye gouge, 7. Removal of entrails, 6. Fingers sliced off, 5. Broken bones, 4. Amputation, 3. Meat hooked, 2. Genital mutilation, 1. Achilles slash

I’m not saying there isn’t some painful stuff on this list, but what’s wrong is it misses the general principle of what makes something painful–an injury is most painful if it stimulates nerves. The more nerves it continuously stimulates, the more painful it is. So injuries in places with a high number of sensory nerves are more painful than those without as many nerves. Yet the way they’re stimulated also matters.

So where do you have a lot of nerves? Your skin (in particular in your hands and feet), your face (in particular your mouth, nose, and eyes), your entrails, your kidneys, and even within your joints and bones. You have very few receptor nerves, ironically, within your brain cavity and not nearly as many in your chest cavity as elsewhere–though your lungs have a fair number of pain receptors. Nor do you have as many pain receptors within your muscles. So injuries to your brain or chest-located-circulatory system, which are the most life-threatening injuries, are not usually the most painful.

And what stimulates those nerves the most? Clean slices, believe it or not, stimulate nerves the least of any major injury. What hurts more is smashing, a.k.a blunt force trauma, mangling (as in an explosion or t-rex bite), and yes, burning!

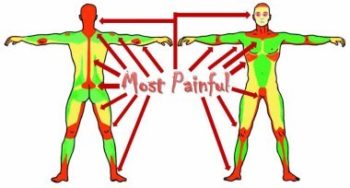

|

| Most painful tattoo sites due to nerve clusters on the surface of the skin and bones nearby. Credit: www.beforeyourtattoo.com |

What doesn’t deserve to be on the list at all? Slit throat, fingers sliced off, and amputation…assuming a person receives these injuries cleanly. Smashing or crushing fingers hurts tremendously (as the time I got my thumb caught in a car door) because you have plenty of nerves in your fingertips. Smashing or stimulating with blunt trauma hurts your throat quite a lot too (as in the time I literally ran full speed into a clothesline and caught it in the neck–playing hide and go seek in the dark as a teen). But a clean slice to the throat probably wouldn’t hurt that much. Note I lost a finger to an accidental amputation as a child. While I was freaked out by the blood, I felt hardly any pain. No kidding.

Likewise a broadsword swiping through a limb and slicing it clean off will not produce all that much pain–especially for hardy medieval types. They probably would not scream at all at such an injury. Note that even a messy and manged amputation may not produce any screaming (I know of people losing limbs in explosions–for most of them as far as I know, they did not scream).

Ok, back to the list above. Will an eye gouge really hurt? That depends. The interior of the eye is actually not full of pain-receptor nerves–but the outer part, the cornea, is. It may sound strange to say it, but certain chemicals or foreign bodies in your eye probably hurts at least as bad, if not worse, as your whole eye being destroyed. If someone gouged your eyeball out of your skull (sorry for the gruesomeness) without scratching the cornea, it might actually not hurt that bad–even if it would be horrible to see. Yet corneal scratches are very painful–because that’s where the nerves are. (So a skilled archer shooting an enemy through the eye probably will not get him screaming–he’ll probably just die–but if he doesn’t die, he probably won’t scream about it.)

How about removal of entrails? The entrails themselves are loaded with pain nerves (as needed to let you know how your digestion is going), so injuries to entrails are well-known to be very painful. Yet being disemboweled without injury to the entrails isn’t as much painful as it’s horrifying and debilitating. Someone with a gut sliced open with a slashing sword will more likely try to hold the guts in or pick them up if they’ve hit the ground than scream helplessly.

Do broken bones hurt? Yes, they do, especially a broken femur (the long bone in your thigh) in part because strong muscles pull on the femur constantly without you being aware of it and if the bone breaks, those muscles are going to continually stimulate pain in the wound by pulling on the bone. But joint injuries infamously hurt as much or sometimes more. Especially a bad dislocation of knees, elbows, or ankles can cause as much or more pain than a bone break.

Injured tendons will also pull up into the body because of muscle tension, like a broken femur. So a ruptured Achilles tendon (which a site providing a “most painful injury” list by a professional football player puts at #2) is extremely painful. But a cleanly sliced one would be less so.

To round out the horror site list, of course “meat hooking” and genital mutilation have the potential to be very painful. The spine has loads of pain receptors and a metal rod shoved up there would hurt all those sensitive spinal disks–unless it severed the spinal cord itself, in which case, it might not hurt much at all. And while the genitals are sensitive to pleasure and also sensitive to pain, a baddie forcing your mouth open and breaking your teeth with a hammer and chisel would almost certainly hurt much, much more than genital mutilation…but when you affect a person’s genitals, there’s a psychological affect as well as a physical one.

|

| An illustration showing a variety of wounds from the Feldbuch der Wundarznei (Field manual for the treatment of wounds) by Hans von Gersdorff, (1517); illustration by Hans Wechtlin. |

Combat Happenings

Sometimes people continue to fight after being seriously or fatally injured–we can say this is especially true for gunshot wounds, which sometimes soldiers report not even knowing they had until the firefight is over. But I can easily imagine someone taking an arrow to the chest and even if seriously injured, not crying out, still fighting. At least for a while.When I see combat scenes from a YouTube compilation from say, Game of Thrones (a series I didn’t watch because of issues I have with some of its content), one thing I note is rather realistically, fights tend to end with big injuries, like a person stabbed through the chest. But from what I see, anyway, the severely injured person almost always cries out. Actually that doesn’t always happen with real injuries.

Note also that while most medieval-style fights ended with one party being severely injured, injuries other than fatal still did happen, where people got hands or fingers smashed, noses cut off, feet spiked though, hard but non life-threatening blows to the head at times. And most of the hardened warriors of the past continued fighting through such wounds. No kidding.

Sometimes a more minor injury would lead to a major one, as a warrior lost the ability to compensate. Yes, sometimes a warrior would realistically scream when mortally injured, depending on if the wound was very painful–but it really was true that non-combatants like women and children screamed more than hardened soldiers or even tough peasants.

Sometimes people would stop fighting without crying out. For example, when people fall from being disemboweled, again, as far as I know, they wouldn’t scream so much as compulsively obsess over keeping in their guts as much as possible. People with a throat cut would put hands to their neck to try to keep the blood in, even if it couldn’t be done. People by instinct usually try to survive their injuries if they can, for example, cradling and squeezing the wrist of an amputated hand.

Usually, when busily engaged in fighting others, the wounded who fell were ignored until the active fighting was over. Historical accounts abound with anecdotes of battlefield injuries in which people lingered for hours or days before dying. I don’t think this is something fantasy stories capture very well. A certain percentage of people would bleed to death, which tends to make people feel cold and causes hyperventilation and loss of consciousness–but it’s not especially painful in and of itself.

But How Does it Feel?

I can imagine someone reading this, thankful perhaps for the info I’ve given, but still feeling dissatisfied. “But how does it feel, Travis?” I can imagine someone asking.

To go back to my own personal experience, I’ve had a number of semi-serious injuries, some of them during military training. But I’ve never been wounded in combat–even though I have been present to help people who were wounded a few times, there are only so many things I can talk about as an insider, based on what I know personally.

Though all non-combat stuff, I’ve had severe ankle sprain, a knee injury, a finger amputation, a hip injury due to a hard fall (at Army Airborne school), a corneal scratch, accidentally impaled a broken branch into my calf, chemical and non-chemical burns, and have smashed my head various times, most notably in a car accident, among other injuries. I know what those things were like for me.

How does any of that feel?

It hurts. I know that’s not helpful, but describing pain is difficult. There are many kinds. To cover any possible injury in detail the obvious thing would be seek out accounts people who have experienced the same wound you want to write about. Or something similar. But bear in mind that the same injury in two different people may not be reported in the same way.

Not only does the type of wound affect how it’s felt, the type of injured individual matters, too. Not everyone feels the same thing or reacts in the same way.

Not only does the type of wound affect how it’s felt, the type of injured individual matters, too. Not everyone feels the same thing or reacts in the same way.

If you would like to talk to me further about any injuries I’ve suffered or seen happen, please let me know in the comments below and I will do my best of accommodate. Or you might have further questions. Or perhaps a reader will have something to add to this discussion, something I forgot to mention. Please free to add your thoughts below.

Comments

Post a Comment